152 million children are in child labour

Today, the ILO estimates that 152 million children are in child labour. Overall, 71 percent of these children are working in agriculture, most them doing unpaid work with their families. The ILO statistics provide an important standard, but it is important to know more about child labour to understand the possible limitations of these numbers.

ECLT has put together data from 9,936 children and 5,481 household heads in our projects in rural communities in Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda, which give us two important takeaways.

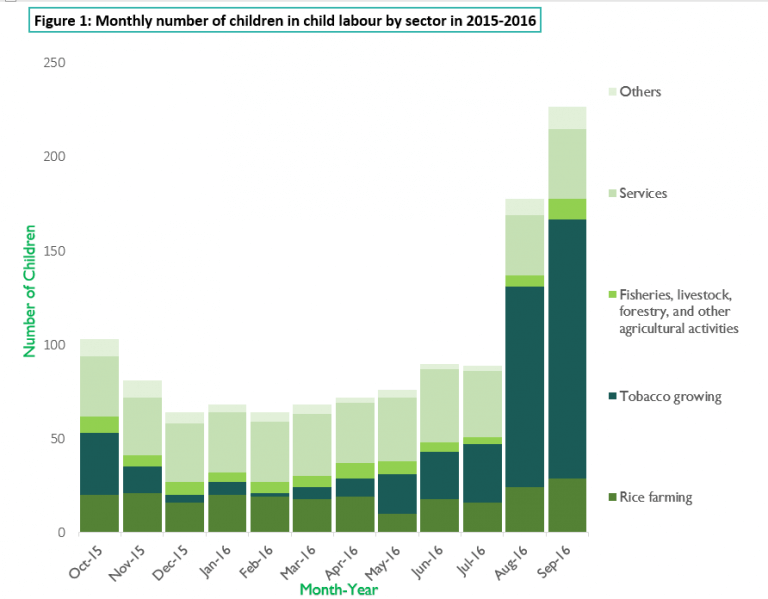

Children’s work is transient and seasonal. This affects how we count workers.

The ILO estimates are based on surveys that look at children’s activities in a reference week. The work done on family farms, however, changes greatly during the year, depending on crops and seasons. Though surveys can give an important glimpse into situations faced by children, looking at a single week does not take into account that work levels change depending on the time of year.

For researchers and practitioners, it is important to note that children may work across different crops and at different rates during the year. Cross-sectional surveys may take information from a particularly high or low period of work and then lead to estimates that are not accurate during most of the year.

Figure 1 provides an example of children’s involvement in hazardous agricultural work in Indonesia. The data shows that children’s work cuts across crop sectors and varies throughout the year.

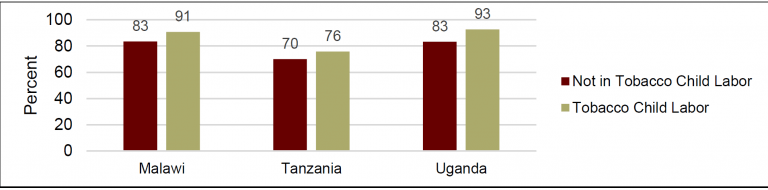

Some children may be in child labour and still go to school

Child labour is “work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child's education, or to be harmful to the child's health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development” (Art. 32 UN CRC) However, it is not clear if children are less likely to go to school if they are not working full time.

In many of ECLT project countries, which are in rural communities in developing countries, school and child labour may not be full-time activities. This means that children may both attend school and be child labourers.

Figure 2 shows information our studies in Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda compares the school status of children aged 5–17 years in child labour in tobacco versus those who are not in tobacco child labour. Consistently across the three countries, children who were engaged in tobacco child labour were in school at higher rates than those who were not in tobacco child labour.

Similar findings have been reported in the literature, leading some scholars to the conclusion that child labour and schooling are not mutually exclusive (e.g. Ravallion and Wodon, 2000; Patrinos and Psacharopoulos, 1997).

This means that school is an important place to reach children about the dangers of child labour and provide support services for students who may be child labourers.

Research is consistently necessary for sustainable solutions

As we continue to seek sustainable and scalable solutions against child labour, it is important to take into account the complex nature of this problem and to share knowledge and best practices. ECLT continues to work directly with local partners and communities to better understand child labour and the realities faced every day by children and families in rural communities.

Media Inquiries: media@eclt.org